Video Sources 8 Views Report Error

Synopsis

After a fateful miss, an assassin battles his employers, and himself, on an international manhunt he insists isn’t personal.

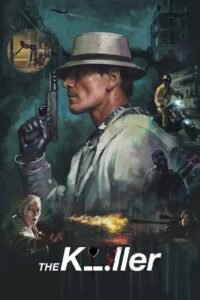

Original title The Killer

IMDb Rating 6.7 216,804 votes

TMDb Rating 6.58 2,535 votes

Director

Director

Cast

The Killer

The Expert

The Lawyer - Hodges

The Client - Claybourne

Dolores

Magdala

Marcus

The Brute

The Target